Recent articles by Charles Lane in the Washington Post, Thomas Friedman in the New York Times and Larry Diamond in the Journal of Democracy agree that the lack of a significant increase in the number of democracies and the measured deterioration of freedoms since 2006 means we are in a global democratic recession. They agree that what the U.S. and other democracies do will make a difference in how the recession develops. In effect, they posit that democratic resolve is being tested – both concerning the state of domestic democracy and democracy's role in international affairs. They are right about that.

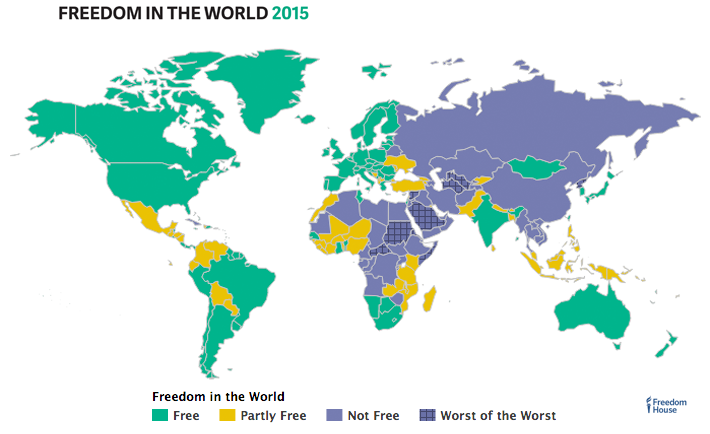

Russian aggression, Chinese assertiveness, Venezuela's encouragement of populist dogmatism, democratic setbacks in Turkey, Hungary, Thailand and elsewhere are all important to the nine-year negative trend on political rights and civil liberties noted in Freedom House’s 2015 Freedom in the World report. So too is the perceived de-emphasis on human rights and democracy among key Western countries – perhaps due to protracted economic difficulties and the challenges presented by extraordinarily violent, well-organized non-state actors who embody authoritarianism. "Realists" and "hard power" advocates (as well as “gradualists,” who see democracy as coming only after economic progress or in increments over decades) use these factors to sideline the importance of democracy and rights advocacy. Those policy debates are not new, but factors are arrayed differently from a few years ago.

The recent lack of dramatic democratic progress witnessed in the 1990s, however, is not the whole picture – and the seeming depression of some over the democratic recession may be because they are missing a huge part of the global canvas. Focusing narrowly on the negative omits the significant number of countries that remain on the democratic track – none without their difficulties, some in serious trouble – and it omits long-established democracies, each also with its serious problems to tackle. Plus, the numerous examples of people coming to the streets demanding democracy and human dignity are left out of the scene. Yes, some of those democratic surges have been reversed (like Egypt), attacked (like Ukraine) or are in small countries (like Burkina Faso), but the examples are not so rare. And, to use a phrase I first heard from Keith Jennings, NDI’s regional director for Southern and East Africa: "We don't see many examples of people out there demonstrating for more authoritarianism."

Importantly, the established expectation now is that countries be democratic. That is a norm that took a long time to develop and should not be cast aside lightly.

Equally important, those who call the present situation the triumph of authoritarianism and lament the demise of democracy as an attractive force are likely as far off as the democracy triumphalists of the ‘90s. The struggle against authoritarianism is neither new nor over – it is just different. A broader historical perspective than one starting in 2006 creates a fuller view.

When World War II ended the battle against horrendous forms of authoritarianism, fewer than a dozen democracies stood as the Iron Curtain rose, military dictatorships proliferated and colonialism sought to regain its footing. The breakthroughs against those trends, including the crumbling of apartheid, took place as a consequence of decades long struggles against oppression and for governments based on popular will. The breakthroughs were not easy; lives were lost, and even after their successes it was not clear in any of the countries whether reversals would follow.

That a large number of recalcitrant autocrats entrenched should not be a surprise, though smartly countering authoritarianism should remain a priority. The instability bread by authoritarianism and its related corruption in places like Egypt cannot be fixed over time with more authoritarianism. Even short-term, difficult trade-offs to fight terrorism or shore up otherwise important interests must be coupled with support for democracy that roots out bad governance, including corruption, and delivers better lives. Rapid authoritarian learning needs to be countered with effective democratic learning and innovation. These are among the crucial lessons of the last 30 years.

Diamond, Friedman and Lane agree that authoritarians use democratic deficiencies in the U.S. and elsewhere to discredit democracy in general. President Obama has echoed the point as well. Those of us who recently watched the movie "Selma" can note that the U.S. has never been an unflawed beacon of democracy, but that has not diminished democracy's attractiveness. Selma also reminds us that the resolve to fix the deepest flaws makes this country a beacon, whether that drive is demonstrated in eliminating barriers to voting rights today, addressing injustice and economic disparity, including racial and other dimensions, or removing other obstacles to dignity.

It's complicated – and it is hard – but building democracy here or in any other country has never been easy. Those who say it was easy were either not in the trenches or have short memories. Building democracy on a global scale is more difficult today than it has been sometimes in the past, though certainly there were darker times than the ones that presently face us.

We don't know how deep or long the democratic recession may be, but as with an economic recession, the “recovery” will be significantly affected by how confident citizens feel about investing their energies in pushing for genuine, effective democracy, and knowing that there is support for their efforts will help. The response to democratic recession should be “democratic stimulus” – smart and determined support for democracy and rights advocacy. That resolve is needed to avoid a “democratic depression” which the world cannot afford.