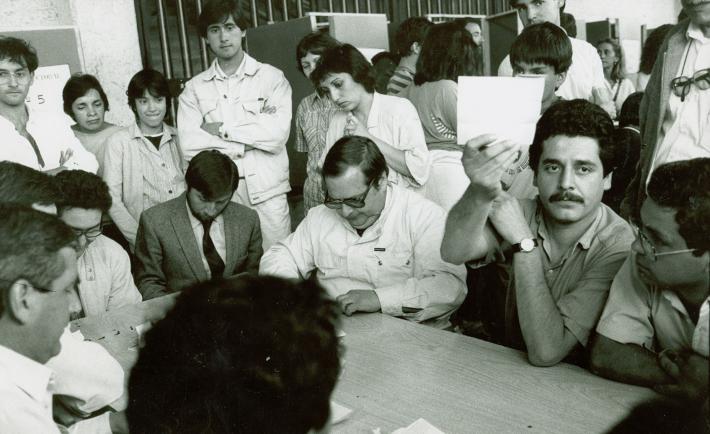

Election workers count votes during Chile’s 1988 plebiscite, which ended Pinochet’s dictatorship. Source: Flickr

When I started out as a junior State Department diplomat at the close of the Carter Administration in the dark days of the Cold War, the state of democracy in Latin America was abysmal. Military dictatorship was the norm throughout the region. During my early State Department years I worked to support, sustain, and contribute to the so-called third wave of democracy in the Americas that helped make the Latin America region, as the Economist recently said, “the most democratic region of the developing world,” behind only North America and Western Europe.

The bipartisan consensus that support for democracy is pillar of America’s foreign policy framework was threaded through my nearly 30 years in the State Department. U.S. leadership on democracy made a positive difference in the past and is still needed today.

As the annual Freedom House survey makes clear, globally, the advance of democratic institutions has stalled and the number of democratic reversals have surpassed cases of democratic gains. Noted scholars of democracy like Larry Diamond point to troubling trends: resurgence of authoritarianism; dismantling of fundamental checks and balances by democratically elected presidents; and the steady erosion of citizen trust in institutions -- a phenomenon aggravated by the spread of social media. Professor Diamond has described this as a global democratic recession, to which neither Europe nor the United States is immune. The Washington Post has tracked the remarkable decline is U.S. citizen trust in institutions over the past two decades.

The bipartisan consensus that support for democracy is pillar of America’s foreign policy framework was threaded through my nearly 30 years in the State Department.

In this setting, Latin America -- with notable exceptions like Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela -- stands out as a region with challenges but where democracy is advancing. Democratic institutions and regular elections have become the regional norm. Military coups have been discredited as a legitimate means to power. Government institutions have become more open and inclusive. New regional norms and mechanisms are in place to promote transparency and democratic governance. Government efforts are flanked by active civil society initiatives to monitor government performance and hold leaders accountable. Despite these positive trends, Latin America’s democratic gains are not assured.

Optimistic researchers used to talk about the 1990s as the decade of democratic consolidation in the Americas. But as NDI has seen in its work in Latin America and around the world, democratic consolidation is always a work in process, with advances and setbacks, hardly linear.

Today the majority of democracies in Latin America are struggling to one degree or another to overcome “second generation” challenges to democracy, most related to weak governance and weak state institutions. In a smaller group of countries, these difficulties are compounded by the more specific threat of authoritarian populism.

Despite millions of people moving into the middle class during the recent commodity super cycle, Latin America remains the most unequal region in the world. Racial and ethnic minorities, women and youth suffer disproportionately high rates of marginalization and violence, particularly in rural areas.

In Latin America, public support for democracy, especially for core institutions like parties and legislatures, has stagnated or fallen as frustrated citizens clamor for an end to poverty, inequality, exclusion, violence -- and increasingly, corruption.

Nobel Prize winner the Peruvian novelist and former presidential candidate Mario Vargas Llosa calls “corruption the biggest threat to Latin American democracies.” Anger over official abuses has fueled protests in many countries and is injecting additional volatility into politics from Mexico to Chile. Brazil’s Car Wash scandal resulted in the impeachment of the sitting president and discredited another. Now, Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht’s supersized bribery has implicated former and sitting presidents and senior officials in multiple countries.

Corruption and its enabler -- impunity from the law -- leaves both weak and even ostensibly stable democracies vulnerable to multiple ills: from political polarization and deteriorating governance to debilitating disruption by criminal gangs and drug traffickers, or to hollowing out from within by authoritarian populists.

Sustaining U.S. engagement and support for democracy in Latin America...is the best way to advance U.S. national interests and remain true to our own democratic values.

Authoritarian regimes can be elected democratically but exercise power in ways that echo the last century’s caudillos and dictators -- as leaders dismantle democratic safeguards, curtail pluralism, and limit freedoms. In Latin America and elsewhere, the new authoritarians are also using a new set of tools to advance their interests, including various forms of electoral espionage, the hacking of politicians and political parties, and the dissemination of misinformation and fake news -- all designed to skew electoral outcomes and to discredit democratic systems.

Sustaining Latin America’s advances on democracy requires more vocal support from leaders in the region and more active participation by citizens at all levels. For those of us in the democracy assistance community, we need to sustain solidarity with democratic activists in places like Venezuela, and amplify and support the welcome leadership of OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro. At the same time, we need to become more adept at understanding and responding to the aggressive attacks against democracy of the new authoritarians using new technologies and social media. Latin America’s democratic progress provides many concrete opportunities for working in partnership to further expand and deepen regional and international networks of pro-democracy activists and to develop new ways to counter corruption, reduce impunity, and strengthen democratic institutions and governance.

Sustaining U.S. engagement and support for democracy in Latin America, at the same time we work to strengthen our own democracy at home, is the best way to advance U.S. national interests and remain true to our own democratic values.