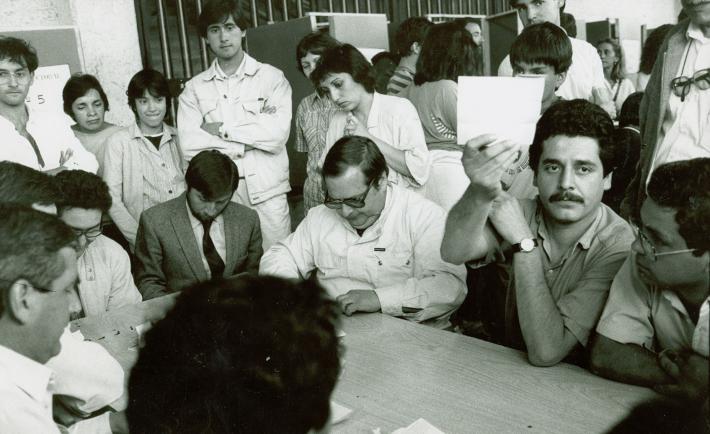

Credit: Dave Taylor

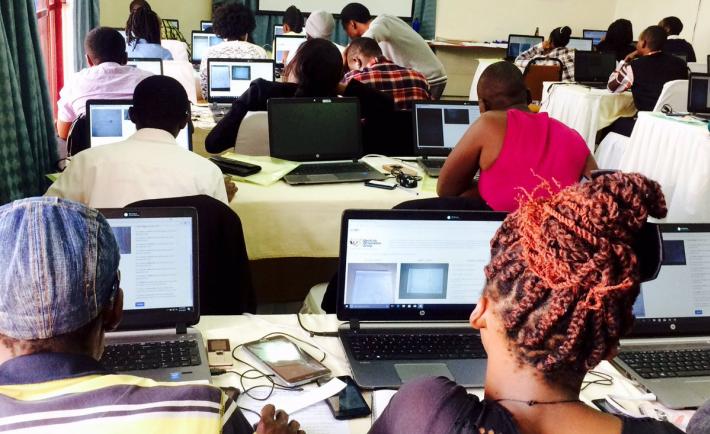

In technology, you often hear geeks referencing the classic “garbage in, garbage out” problem. When the inputs to a system are bad, however beautifully crafted the program itself may be, the outputs will necessarily be bad as well. Our democratic systems are dependent on the input of citizens, but when disinformation is also an input the outputs of our processes can be deeply flawed. Disinformation and the systemic distrust it fuels has been a dangerous ingredient in the global surge of nativism, intolerance, and polarization undermining democracy and human rights around the world. Understanding and stopping disinformation is a tremendous challenge; any single solution will be incomplete so many will be required. In 2018, the fastest, most virulent and dangerous disinformation is spreading on digital platforms, and as such technical understanding is critical to wrap our heads around the problem.

_1_0_0_0_0_0.jpg)