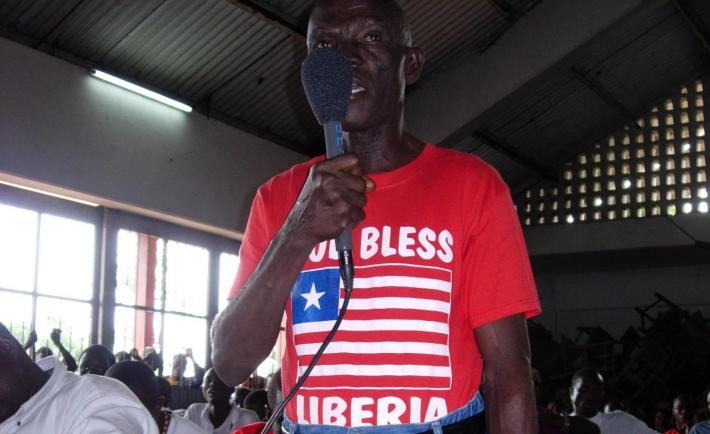

Citizens ask questions of candidates during NDI-supported senate debates in Liberia during the 2005 elections. Credit: Jim Della-Giacoma

Can there be peace without the United Nations? Maybe. Resilient democracies might also exist without direct intervention from international organizations. But given that NDI’s Resilient Democracy blog series was launched on the UN International Day of Peace, it would be useful to consider the role of international organizations and the evolving ideas they are promoting about sustaining peace and peaceful societies. Connecting to the UN’s macro thinking could strengthen NDI’s micro-level work.

There are two key milestones worth noting as a part of this reflection on peace and democracy. In September 2015, every member of the United Nations signed up to the sustainable development goals, including SDG 16 to “promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels”.

Then, in April 2016 the UN General Assembly and UN Security Council agreed to rare joint resolutions on sustaining the peace. Once again, the universality of support for this international legislation is important. Here you have every country “stressing that civil society can play an important role in advancing efforts to sustain peace.” What’s more, the resolution goes on to emphasize “the importance of a comprehensive approach to sustaining peace, particularly through the prevention of conflict and addressing its root causes, … national reconciliation and unity including through inclusive dialogue and mediation, access to justice … accountability, good governance, democracy, accountable institutions, gender equality and respect for, and protection of, human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

Looking back at the stories in NDI’s blog series, I see each post in its own way resonating with these larger agendas. In the first post in the series Kristen Wall wrote “political institutions must generate and implement inclusive policies and practices that deliver public goods – such as security, educational and economic opportunities, justice, and respect for individual and collective rights – equitably across diverse social groups.” Lindsay Robinson wrote about lessons learned on promoting peaceful elections in Cote d’Ivoire. Ben Malick contributed his piece showing how NDI had built bridges in communities with inter-group tensions. Leila Stehlik-Barry addressed the serious threat that violence and crime pose not only to citizens but the institutions that govern them. Austin Robles looked at the Institute’s work in Colombia “fostering reconciliation and building peace”.

This series shows that the new international agenda is at one with NDI’s work, but it struck me that while only 200 miles (350 km) apart, these significant shifts in how the world talks about peace at the UN in New York are not travelling across the Delaware River. While the work in practice may be consistent, the language and frameworks we use are not.

Why is this so? The international development and peacebuilding communities are intellectually self-siloing ourselves. Faced with the prospect of information overload this is, at one level, a survival strategy. But there is also a self-separation between the doers and the policy people; the headquarters and the field. In tuning out of each other’s conversation, we are missing the opportunities to mutually reinforce each other. It should be an unnatural divide as the big ideas are leading to renew efforts to implement and make a difference in the lives of people around the world.

But there are important reasons to resist this separation, dismantle the stovepipes, and better utilize the evolving international language on peace, conflict, and development.

First, is legitimacy. In my experience, the work of a UN peace operation or NDI democracy program can be made or broken depending on the perception of the legitimacy and standing of those providing the ideas and support. The standing of those looking to support resilient democracies is often questioned by host governments and even partner communities, but understanding how this work fits into the universal agendas of the SDGs or Sustaining Peace agenda and being equipped to explain it can boost the legitimacy of these programs, projects, and activities.

Secondly, these are processes that each and every nation has signed onto in New York. NDI’s work at the micro level could benefit from being connected to this macro level agenda.

Understanding the universality of these ideas and how they fit together could open up a world of possibilities for local and global partnerships, including material support. If we think they have merit, then we need to recommit to spreading them. The United Nations, NDI, and the communities for whom we all work with would be better off for it.