Equal participation of citizens in politics is essential for strengthening democracy. Citizen participation must be inclusive, representative and intercultural. One of the foundations of democracy is respect for human rights, which includes recognition of individual and collective rights of indigenous peoples. And one of these collective rights lies precisely in the use of indigenous languages. This is especially true in Guatemala, where indigenous peoples represent a large and diverse, but frequently marginalized, population.

Article 16 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which has been ratified by Guatemala, affirms that “indigenous peoples have the right to establish their own media in their own languages and to have access to all forms of non-indigenous media without discrimination.”

In Guatemala, despite the fact that according to some estimates the majority of the population is indigenous (the official census in 2011 estimates at least 40 percent), the Guatemalan government has failed to guarantee services to Mayan peoples in their own language. This is one of the reasons why many indigenous languages are in danger of disappearing, which would mean the extinction of an important cultural and ancestral legacy.

Public services such as education and health, as well as economic transactions and many social relations, at the national level in Guatemala are only available in Spanish. This is ultimately a form of linguistic discrimination.

In addition to extinction, when a government does not guarantee that people are provided services in their native language, there are other consequences that entrench exclusion and increase discrimination within a society. One result is that many families do not speak their first language in their own homes in an effort to prevent future generations from experiencing discrimination within society or by the system itself, which further contributes to declining use of the language. This is a social issue that is most harmful for young Mayans who gradually lose the fundamental elements of their identity and their right to express themselves as members of indigenous groups.

One of the foundations of democracy is respect for human rights, which includes recognition of individual and collective rights of indigenous peoples. And one of these collective rights lies precisely in the use of indigenous languages.

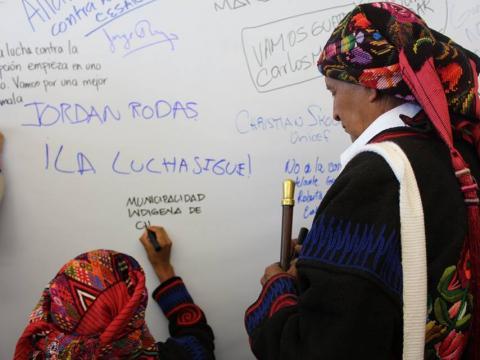

This is why efforts to strengthen and reclaim languages are necessary and urgent. It is necessary to recognize the fundamental role that media plays as a vital tool for younger generations in reconciling and understanding their identity. Strengthening democracy requires the democratization of words.

It is therefore fundamental that the government and public institutions, as well as the private sector, ensure the use of indigenous languages in their programs in order to comply with the Agreement on the Identity and Rights of Indigenous Peoples that is part of the peace accords signed in 1996. Compliance with the provisions of these accords is a first step towards recognizing the diversity that exists in Guatemala and in building a truly multilingual state.

The Citizen Action (Acción Ciudadana) and Electoral Watch (Mirador Electoral) observation projects were designed to be implemented in the Mayan languages spoken in predominantly indigenous municipalities. In addition, the Mirador Electoral coalition observed the treatment of indigenous citizens by electoral authorities and if those citizens faced difficulties exercising their right to vote due to language barriers. Reports from international observation missions, such as the Tikal Protocol and the Organization of American States, included recommendations on the need to improve access to voting in native languages, which were also included in the Mirador Electoral findings.

It is for these very reasons that we believe that it is necessary to publish the stories of the observers in their native languages. We recognize the importance of being able to share their experiences with members of their communities in their own language. You can find the articles published in Mayan languages at the following links: K'iche (introduction) /// Mam (electoral violence) /// Ixil (gender-based violence) /// Kaqchikel (importance of Mayan languages) /// Kaqchikel (election transparency) /// Q'anjob'al (youth participation) /// K'iche (what's next)